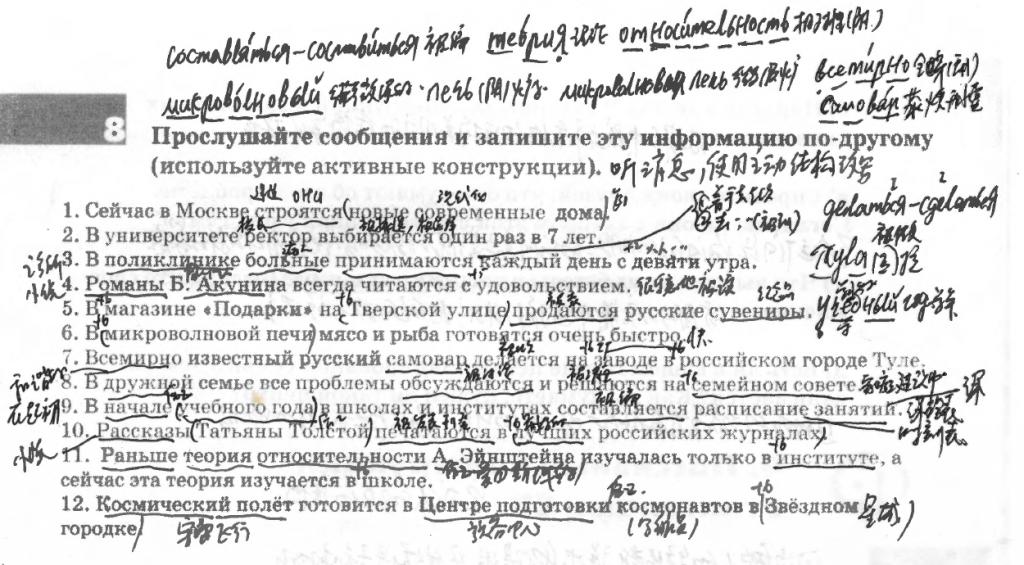

完成体动词被动结构 必须用被动形动词

| 动词 | 被动结构 |

| нсв | нсв_ся |

| св | 必须用被动形动词 |

| построить | св | 修建 |

| построенный | 被动形动词 | 被修建的 |

| построен | 短尾 | 被建造 |

| 现在时 | построен (+а, +о,+ы) | 房子在被修建 |

| 将来时 | будет / будут построен (+а, +о,+ы) | 房子将被修建 |

| 过去时 | был(+а,+о,+и) построен (+а, +о,+ы) | 房子被修建了 |

一步一步学俄语

完成体动词被动结构 必须用被动形动词

| 动词 | 被动结构 |

| нсв | нсв_ся |

| св | 必须用被动形动词 |

| построить | св | 修建 |

| построенный | 被动形动词 | 被修建的 |

| построен | 短尾 | 被建造 |

| 现在时 | построен (+а, +о,+ы) | 房子在被修建 |

| 将来时 | будет / будут построен (+а, +о,+ы) | 房子将被修建 |

| 过去时 | был(+а,+о,+и) построен (+а, +о,+ы) | 房子被修建了 |

1 )

1 Виктор Михайлович Васнецов 维克多 米哈依洛维奇 瓦斯涅佐夫 переезжать – переехать (乘车、马、船等)越过、驶过、通过;搬往,迁往

2、Троицкий 特洛伊茨基的 переулок 胡同,小巷 построить修建

3、完成体动词被动结构 必须用被动形动词 построить – построенный -построен был(+а,+о,+и) построен (+а, +о,+ы) 被修建了 по+3 按照 проект 方案 设计,规划,图纸,设计图,设计书,草案,方案,工程项目,计划 самый 亲自的

4、мебе́ль 家具 ь阴性 сделать -сделанный – сделан родной 亲近的 Аркадий 阿尔卡季 被谁 用五格

2、)

1、伟大的科学发明

2、 созда́ть-со́зданный-со́здан(-а,-о,-ы) 被创作;被创建(过去时был/была/были+ ;将来时 будет/будут + ) он – им5格

3、同一时代的人 惊奇удивляться – удивиться кому-чему或на кого-что对谁/什么表示惊奇 要知道 仅仅是

4、立刻 сразу

5 приня́ть- (-нять) – при́нятый – при́нят (прнята́, при́нято, при́няты )被接受;被采纳 大年级

3、)

1、 众说周知 написа́ть- напи́санный – написан (-а,-о, -ы)被写完

2、结束 (св) зако́нчить – зако́нченный – зако́нчен ( -а -о -ы )

3、смерть死亡 之后 после+2 над+5 表示行为所涉及的对象,属于; произведение 作品,产物,著作

4 )

периодический 周期的,周期性的 / закон 法律,规律,法则 / элемент 化学元素

периодический закон химических элементов 化学元素周期律

открыть 打开,发现,揭露 св – откры́ть – откры́тый -откры́т ( -а -о – ы )被发现

таблица химических элементов 化学元素表

(существовать 存在 )существует легенда 传说

видеть что во+6 сне 梦见(在梦里看见)сон 梦

第一段

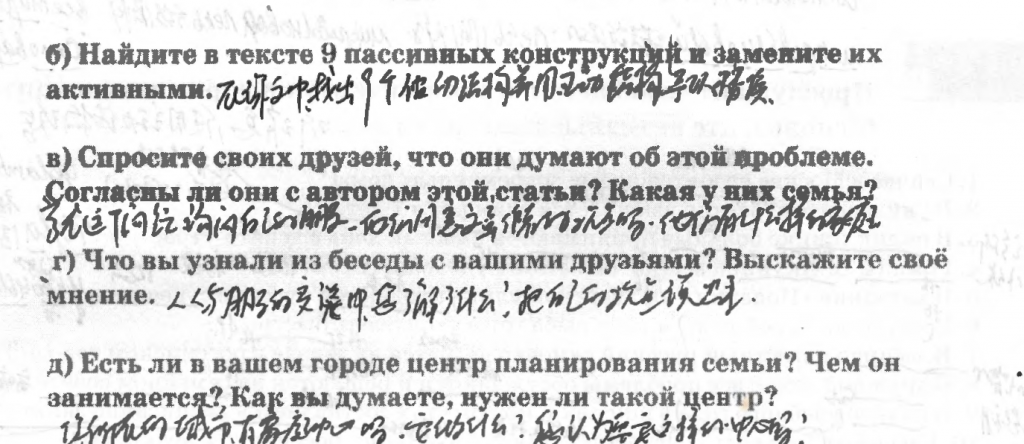

1、现在几乎所有的俄罗斯城市都建有家庭计划中心。почти几乎 2、создаться 被创建 3 плани́рование 计划,规划 4 这些中心接待的都是一些年轻人,一些渴望从心理师、医 生、教育工作者那里得到人生建议的年轻人。консультация (被咨询者的)意见,(对质疑的)解答 консультант/ консультантка 顾问 консультативный 咨询的 协商的 консультировать(кого或无补语)给…答疑,解答疑问,进行辅导 с кем-чем 向…咨询 консультироваться с кем-чем 征求…意见,咨询,质疑 5 опытный 有经验的 心理师、医 生、教育工作者 6 讨论 7 在这些中心讨论的都是年轻家庭里的焦点问题: 物质难题、住房难题以及孩子的生育与教养难题。наибо́лее 特别地,最,(副) (常与形容词、副词连用, 构成最高级形式) 8 物质难题、住房难题以及孩子的生育与教养难题 материя 物质 материальный 物质的 материализовать 使…具体化 жильё 住房,住所 рождение 出生 воспитание 教育 ребенок

第二段

在最近这段时间里心理师和教育工作者们经常会讨论一个话题:一个家庭里蔽好有几个孩子?一个还是更多?每个家庭都有自己的看法。1 最近 2 心理师和教育工作者们 3 一个还是一些 4 по-своему 以特殊方式,按自己的方式

第三段

1 多子女家庭在现代社会已经不流行了。многоде́тный 子女多的 выйти из мо́ды 过时 2 现在人们普遍认为生一个孩子才是最明确最适宜的选择。счита́ться-счесться(特殊-сть)(被)认为 3 一个孩子也 就意味着他可以得到家里大人们大部分的时间与关注,他的物质生活就可以得到保障。уделяться (被)抽出,(被)分出 нсв I кому-чему больше 更多的 4 лучше (хороший,хорошо的比较级)更好 物质生活就可以得到保障 5 但是那些独生子女家庭里 的孩了,尤其当他们半大不大的时候,经常会感觉自己一个人很孤单。独生子女 подросток 少年(12-17) одиночество 孤单 6 这些孩子们 表现的很不自信很不独立 неуверенный себе в+6 对自己不自信 сила 力量 7 因为他们已经习惯于被家里的爸爸妈妈们,爷爷奶奶们所照顾着。опекаться (被)照管,(被)看管,(被)关心;(被)监护 постоянно 习惯

第四段

1 当然,当 一个家庭里有许多孩子的时候,家 长们不可能分摊很多时间到每一个孩子身上。проводить度过 2 但是在多子女家庭, 经常一起玩的哥哥姐姐们可以给小一点的孩子起到榜样作用,从而教育他们。воспитаться – воспитаться (被)教育;(被)培养 在大家庭成长起来的孩了总是会很快变得独立与自信。становиться (用作系词)成为 самостоятельный 独立的

There is no sequence of tenses in Russian whatsoever.

The information in a subordinate sentence is understood to be relative to the main clause:

So if the piece of information is simply about where things are or what someone does, use present tense in the subordinate clause.

Use the particle “ли” in reported questions or situations when you don’t know which option is true:

The particle is attached to the word that is in doubt. It needn’t be a verb, for instance, «Я не зна́ю, в Москве́ ли он» (i.e. whether he is in Moscow or in some other city). «Ли» generally attaches to the first stressed word of the clause.

The verb говори́ть is used both as “to say, to tell” and as “to talk, to speak”. When you report someone’s words, obviously, the 2nd meaning is in action:

Russian has a whole set of perfective verbs. Usually you arrange verbs neatly into closely matching pairs of imperfective + perfective. And these are different for the two meanings of «говори́ть»:

Remember «Скажи́те, пожа́луйста … » ?

Rather than referring to ongoing actions or past(future) actions in general, perfective verbs refer to actions in a point-wise manner, ignoring the action’s inner structure. That is, such “singular” actions happen at some particular “moment” and can be conveniently arranged in a sequence when telling a story. This distinction is about to come into focus in one of the following skills.

Being too lazy to make up many different verbs, we usually make new ones based on the old ones. The vast majority of unprefixed verbs are imperfective.

The last phenomenon is known as suppletion and only happens for a limited number of verbs and their derivatives. The English verb “to go” is another example of such behavior (its past form is “went”).

Note that suffixation is very popular for secondary imperfectives. Usually only one prefixed verb is considered an “ideal match” for an imperfective verb. Others are somewhat different in meaning (or a lot different). But you need imperfective partners for these, too, so Russian uses suffixes for that:

The verb «мочь» is used to talk about the general possibility of something, and also, very often—about your ability to perform something and reach some result. Perfectives are used in this second meaning:

We do not use мочь for skills. Russian has уметь for this.

Both mean “again” and are largely interchangeable when they mean that an action from the past has occurred again.

«Опять» is more popular but it’s focused on staying “the same as before”. «Снова» (cf. «новый») can also mean action performed “anew, from the beginning”.

Only «опять» is used in «опять же» (~”besides”).

When asking someone to repeat, use «ещё раз».

imperfective verbs

Perfective verbs describe events: singular, definite actions that are viewed as localized in time. They “happened” at some moment (“I made a video”, “I slept for some time and then went outside”). Or they describe a certain change of state at some “turning point” (not yet eaten→eaten, not slept enough→slept enough and ready to get up).

It is argued in a few works that “a natural” perfective is just a prefixed verb where a prefix’s metaphorical meaning so conveniently overlaps the verb’s own meaning, that you cannot feel any change. So don’t be surprised if some vague actions have several perfective matches for a single imperfective verb.

That also means that sometimes you’d better memorize a pair even if it is technically a “poor” match. After all, in some contexts it will come in handy:

Ба́ня – э́то ме́сто, куда́ ру́сские лю́ди хо́дят, что́бы рассла́биться, встре́титься с друзья́ми и помы́ться. Ба́ня о́чень похо́жа на са́уну, но име́ет свои́ осо́бенности. Ка́ждый тури́ст до́лжен сходи́ть в ба́ню!

Настоя́щая ба́ня – э́то о́чень хорошо́ для здоро́вья и о́чень интере́сно. Ита́к, в чём ра́зница ме́жду ба́ней и обы́чной са́уной? Са́мое гла́вное – э́то ве́ник. Ве́ник – э́то свя́зка молоды́х ве́ток како́го-нибу́дь де́рева (обы́чно берёзы, пи́хты и́ли ду́ба). Ру́сские лю́бят брать в ба́ню ве́ник из берёзы и массажи́ровать им друг дру́га. Это прия́тно и поле́зно для здоро́вья.

Лю́ди сидя́т в ба́не до́лго, до того́ моме́нта, когда́ им так жа́рко, что они́ уже́ не мо́гут терпе́ть. Тогда́ они́ выбега́ют из ба́ни на у́лицу и пры́гают в снег, что́бы охлади́ться. В совреме́нных ба́нях есть бассе́ин вме́сто сне́га. В э́том бассе́ине вода́ о́чень холо́дная. По́сле ба́ни ру́сские лю́бят пить чай и разгова́ривать.

The Russian sauna is a place where Russians go to relax, meet friends and wash themselves. Banya is very similar to a sauna but has its own peculiarities. Every tourist should visit a banya!

A real banya is very good for health and very interesting. So, what is the difference between a Russian sauna and the common sauna? The most important one is the “venik”. A venik is a bunch of green twigs from a tree (usually birch, fir tree or oak). Russians love taking to the banya a venik from birch and massage each other with it. That is pleasant and healthy.

People stay in a banya for a long time, until the moment when they feel so hot that they cannot bear it any longer. Then, they run out of the banya outside and jump into the snow in order to cool down. In modern banyas there is a swimming pool instead of snow. In this swimming pool the water is very cold. After banya, Russians like to have tea and chat.

Cанкт-Петербу́рг – э́то оди́н из са́мых краси́вых городо́в Росси́и. Он был осно́ван импера́тором Петро́м I (пе́рвым). Импера́тор реши́л постро́ить го́род здесь, что́бы откры́ть для Росси́и «окно́ в Евро́пу».

В Санкт-Петербу́рге есть о́чень мно́го краси́вых дворцо́в, музе́ев и церкве́й. Здесь нахо́дится изве́стная янта́рная ко́мната. Ле́том в Санкт-Петербу́рге быва́ют «бе́лые но́чи».

Ра́ньше на э́том ме́сте бы́ло боло́то, поэ́тому постро́ить го́род бы́ло о́чень тру́дно. О́чень мно́го люде́й у́мерло, когда́ стро́или э́тот го́род. Поэ́тому говоря́т, что э́то «го́род на костя́х».

Э́то дни, когда́ но́чью на у́лице почти́ так же светло́, как днём. Э́то са́мое популя́рное вре́мя для тури́стов. Но́чью на у́лицах мно́го люде́й и ка́жется, что весь го́род не спит.

Before, in this place there was a swamp, that is why it was very hard to build the city. Many people died while building this city. That is why they say that this is a “city on bones”.

Saint Petersburg is one of the most beautiful cities of Russia. It was founded by the emperor Peter I. The emperor decided to build a city here in order to open a “window to Europe” for Russia.

In Saint Petersburg there are many beautiful palaces, museums and churches. The famous amber chamber is located here. In summer in St-Petersburg occur the “white nights”.

These are days when outside at night it is almost as light as during the day. This is the most popular time for tourists. At night there are a lot of people in the streets and it seems that the whole city doesn’t sleep.

Са́мое холо́дное ме́сто в ми́ре – э́то ру́сская дере́вня Оймяко́н. Э́та дере́вня нахо́дится на восто́ке. Там живёт о́коло 500 (пятисо́т) челове́к. Зимо́й обы́чная температу́ра – ми́нус 50 (пятьдеся́т) гра́дусов. Одна́жды в э́той дере́вне бы́ло ми́нус 71 (се́мьдесят оди́н) гра́дус! Но жи́тели дере́вни привы́кли к хо́лоду. Здесь все друг дру́га зна́ют. Все друг дру́гу помога́ют.

Люби́мое ме́сто встре́чи – в магази́не, где продаю́т све́жий хлеб. В дере́вне нет ба́ра, так как по́сле 18:00 (шести́) часо́в нельзя́ продава́ть ни во́дку ни пи́во. Пья́ный челове́к мо́жет умере́ть на у́лице от хо́лода о́чень бы́стро…

Зимо́й день дли́тся всего́ 3 (три) часа́. А ле́том светло́ да́же но́чью. В ма́рте в дере́вне быва́ет фестива́ль. На э́тот фестива́ль приезжа́ет мно́го иностра́нцев. Они́ хотя́т почу́вствовать, что тако́е -50 (ми́нус пятьдеся́т) гра́дусов.

The favourite meeting place is at the shop where they sell fresh bread. In the village there is no bar because after 6 p.m. it is not allowed to sell either vodka or beer. A drunk person can die in the street very quickly…

The coldest place in the world is the Russian village of Oymyakon. This village is situated in the East. Around 500 people live there. In winter the usual temperature is minus 50 degrees. Once in this village the temperature reached minus 71 degrees! But the inhabitants of the village are used to the cold. Here everyone knows each other. Everyone helps each other.

In winter a day lasts only 3 hours. And in summer it is light even during the night. In March there is a festival in the village. Many foreigners come to that festival. They want to feel what -50 degrees is.

Не́которые иностра́нцы ду́мают, что в Росси́и медве́ди хо́дят по у́лицам. Коне́чно, э́то непра́вда! Медве́ди живу́т в лесу́ и не лю́бят люде́й.

Встре́ча с медве́дем мо́жет быть о́чень опа́сна. Ру́сские лю́ди лю́бят ходи́ть в лес и собира́ть грибы́и я́годы. Они́ де́лают э́то с осторо́жностью, так как медве́ди то́же о́чень лю́бят я́годы и мо́гут напа́сть на челове́ка. Медве́дь ест всё: я́годы, ры́бу, мя́со и да́же насеко́мых. Осо́бенно он лю́бит мёд.

Зимо́й медве́ди обы́чно спят, потому́ что пого́да сли́шком холо́дная и нет еды́. Пока́ медве́дь спит, он мо́жет похуде́ть на 80 (во́семьдесят) килогра́мм! Ру́сские лю́ди о́чень похо́жи на медве́дей. Зимо́й они́ то́же стано́вятся медли́тельными и мно́го спят, потому́ что на у́лице сли́шком хо́лодно и темно́.

Поэ́тому ру́сские лю́бят медве́дей и называ́ют их “ми́шки”. Ми́ша – э́то талисма́н ле́тней олимпиа́ды1980 (ты́сяча девятьсо́т восьмидеся́того) го́да в Москве́.

Some foreigners think that in Russia bears walk along the streets. Of course, that is not true! Bears live in forests and do not like people.

An encounter with a bear can be very dangerous. Russians love going to the forest and collecting mushrooms and berries. They do it carefully because bears love berries too, and they can attack a person. A bear eats everything: berries, fish, meat and even insects. Particularly, they love honey.

During the winter, bears usually sleep because the weather is too cold and there is no food. While sleeping, a bear can lose 80 kilos. Russian people resemble bears very much. In winter they also become slow and sleep a lot because it is too cold and dark outside.

That is why Russians love bears and call them “mishki”. Misha is the mascot of the 1980 Summer Olympic Games in Moscow.

Шу́тка про медве́дя:

Холо́дная зима́. Медве́дь бро́дит по́ лесу, иногда́ остана́вливается, стучи́т голово́й о де́рево и кричи́т: “Ну заче́м, заче́м я пил сто́лько ко́фе!?”

Joke about a bear::

Cold winter. A bear wanders around the forest, stops from time to time, hits its head against a tree and yells: – But why, why did I drink so much coffee?!